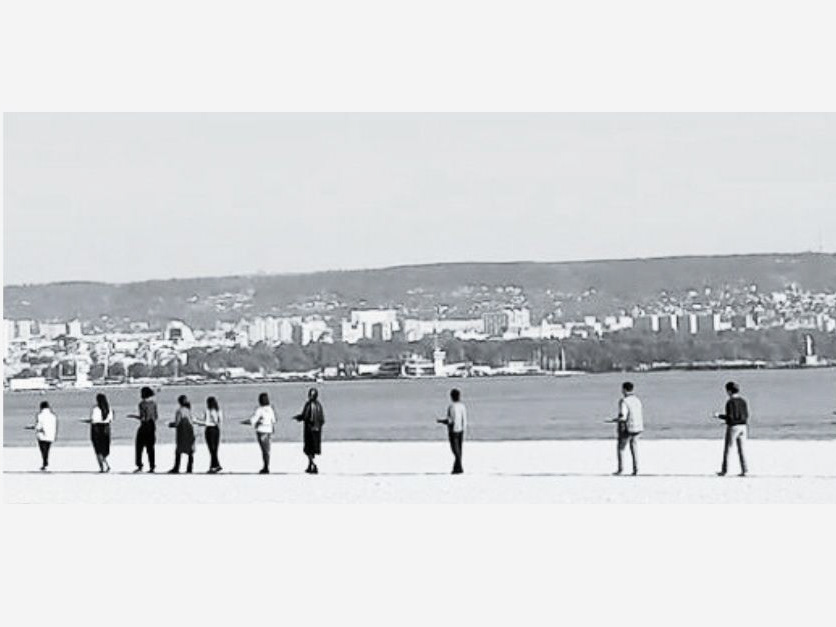

photo credits: Martin Atanasov

Highlights from the research around the topic of UTOPIA in the production frame HABITAT placed in Moving Body platform '2022

RESEARCH

<No place. to be> is a research residency on the contemporary dimensions of utopias. In the first research stage, I invited five artists to reflect on the topic, each through their own medium – writing - Yasen Vasilev (BG), photography - Martin Atanasov (BG) , generative audiovisual - Pandelis Diamantides (CY/ NL), choreography and movement - Johannes Schropp (DE)

Each of them offered a different perspective on utopia:

- a political re-invention

- a personal and psychological inner utopia

- a disillusionment and critical distance from the concept of utopia

- a practice and maintenance of utopian thinking, rather than production

- an indigenous and spiritual understanding of utopia

YIN UTOPIA

Ursula Le Guin

It would be

dark,

wet,

obscure,

weak,

yielding,

passive,

dark,

wet,

obscure,

weak,

yielding,

passive,

participatory,

circular,

cyclical,

peaceful,

nurturant,

retreating,

contracting,

circular,

cyclical,

peaceful,

nurturant,

retreating,

contracting,

The title starts from the understanding that the space for living and being is ever shrinking. In the ruins of capitalism, spaces have become unbearable, inhospitable, and uninhabitable. “The West isn’t made for human life. In fact, there’s only one thing you can really do in the West, and that’s to make money.” (Michel Houellebecq). If we are pushed out of our habitat and if there’s no place for us, we need to imagine it and create it “out of the pure urge of survival” (Slavoj Zizek).

No place is the literal translation of utopia. To be is the performative magical spell-like ritual of the uttering that makes things appear through language. The attempt to embody the utopian in the research itself brought about this manual. It collects and describes a series of practices that we borrowed, invented, investigated, shifted, tried out, and failed with during the residency. It also offers a series of questions that we don’t have the answers to yet, as well as a bibliography for reference and further reading.

I aim to use this manual for the activation of a long-durational immersive participatory performance blurring the difference between art and life, taking the final fifth indigenous and spiritual understanding of utopia. The manual also to function as a guideline for the audience on how to look at and perceive reality and catch a glimpse of utopia. In the words of Ursula K. Le Guin this utopia “would be dark, wet, obscure, weak, yielding, passive, participatory, circular, cyclical, peaceful, nurturant, retreating, contracting, and cold.”

How can we shed light differently on everyday places that we inhabit that potentially contain a hidden utopia as a no-place – how can we see them as strange and new and magical? “Mystery suggests a rich and ambiguous range of terms: secret, enclosed, withdrawn, unspeakable.” (Timothy Morton). How can we heal and change the perspective on the spaces through our practices of being?

A practice of being includes unlearning, re-shaping, distorting, confusing, and healing our bodies in those spaces. It aims to illuminate them in different ways so that they reveal the potential of a utopian no place.

We explore the positions, relations, and actions of the body in these spaces. We tune in to the invisible no place in space. We are looking for a specific sense of time outside of time, connected to the sacred, the heterotopia, the community carnivals, and the festivities.

We use language for its magical properties, its spell-like potential, its performative function, where utterings create new realities.

2023

In the second part of the research, I developed the concept around PRACTICES FOR ALTERED STATES.

To allow time + space + body to melt together

Practices for Altered States enables me to re-enter the vocabulary, music, philosophy, mythology, and somatics of the dance, to more deeply comprehend what it teaches about the body, and the body’s inner and outer relations in dance and everyday life.

By doing this I learn to stay present, unlearn, and relearn meanings attached to the self and the source - the essence, as the practices for altered states require an openness towards what is being listened to.

From the Pendulation Practice, I developed a choreographic dance performance called Reflections

photo credit: Martin Atanasov

Further notes on the research '2023

Planting seeds and growing herbs and flowers can teach us a lot! It’s like practicing the cycle of life again and again, noticing and observing the quiet miracles happening before your eyes, practicing 'gift economy'.

What is 'gift economy'? When I was a kid one of the first things that shaped my view of a world, full of gifts simply scattered at your feet, was Apple trees ... A gift comes to you through no action of your own, free, having moved toward you without your beckoning. It is not a reward; you cannot earn it, or call it to you, or even deserve it. And yet it appears. Your only role is to be open-eyed and present. Gifts exist in a realm of humility and mystery—as with random acts of kindness, we do not know their source.

What if we experience the world in that time as a gift economy, “goods and services” not purchased but received as gifts from the earth?

More thoughts on 'gift economy' in capitalistic society, we can learn by the language and behaviour of the plants and adopting the “philosophy” of their existing and communication.

A seed neither fears light, nor darkness, but uses both to grow, they don’t die when you throw ‘dirt’ at them, they grow and when seeds want to rise they drop everything that is weighing them down.

Some studies of mast fruiting have suggested that the mechanism for synchrony comes not through the air, but underground. "The trees in a forest are often interconnected by subterranean networks of mycorrhizae, fungal strands that inhabit tree roots. The mycorrhizal symbiosis enables the fungi to forage for mineral nutrients in the soil and deliver them to the tree in exchange for carbohydrates. The mycorrhizae may form fungal bridges between individual trees, so that all the trees in a forest are connected. These fungal networks appear to redistribute the wealth of carbohydrates from tree to tree." A kind of Robin Hood, they take from the rich and give to the poor so that all the trees arrive at the same carbon surplus at the same time. They weave a web of reciprocity, of giving and taking. In this way, the trees all act as one because the fungi have connected them. Through unity, survival. All flourishing is mutual. Soil, fungus, tree, squirrel, boy—all are the beneficiaries of reciprocity.

Hopefully more and more we can think about language in a much broader perspective too, not only from animal-human one.

Why it seems that in our modern world it is hard to adopt the principle of a mycorrhizal network that unites us, an unseen connection of history and family and responsibility to both our ancestors and our children. As human beings, can we stand together for the benefit of all.

We are remembering what they said, that all flourishing is mutual.

What if we experience the world in that time as a gift economy, “goods and services” not purchased but received as gifts from the earth?

More thoughts on 'gift economy' in capitalistic society, we can learn by the language and behaviour of the plants and adopting the “philosophy” of their existing and communication.

A seed neither fears light, nor darkness, but uses both to grow, they don’t die when you throw ‘dirt’ at them, they grow and when seeds want to rise they drop everything that is weighing them down.

Some studies of mast fruiting have suggested that the mechanism for synchrony comes not through the air, but underground. "The trees in a forest are often interconnected by subterranean networks of mycorrhizae, fungal strands that inhabit tree roots. The mycorrhizal symbiosis enables the fungi to forage for mineral nutrients in the soil and deliver them to the tree in exchange for carbohydrates. The mycorrhizae may form fungal bridges between individual trees, so that all the trees in a forest are connected. These fungal networks appear to redistribute the wealth of carbohydrates from tree to tree." A kind of Robin Hood, they take from the rich and give to the poor so that all the trees arrive at the same carbon surplus at the same time. They weave a web of reciprocity, of giving and taking. In this way, the trees all act as one because the fungi have connected them. Through unity, survival. All flourishing is mutual. Soil, fungus, tree, squirrel, boy—all are the beneficiaries of reciprocity.

Hopefully more and more we can think about language in a much broader perspective too, not only from animal-human one.

Why it seems that in our modern world it is hard to adopt the principle of a mycorrhizal network that unites us, an unseen connection of history and family and responsibility to both our ancestors and our children. As human beings, can we stand together for the benefit of all.

We are remembering what they said, that all flourishing is mutual.